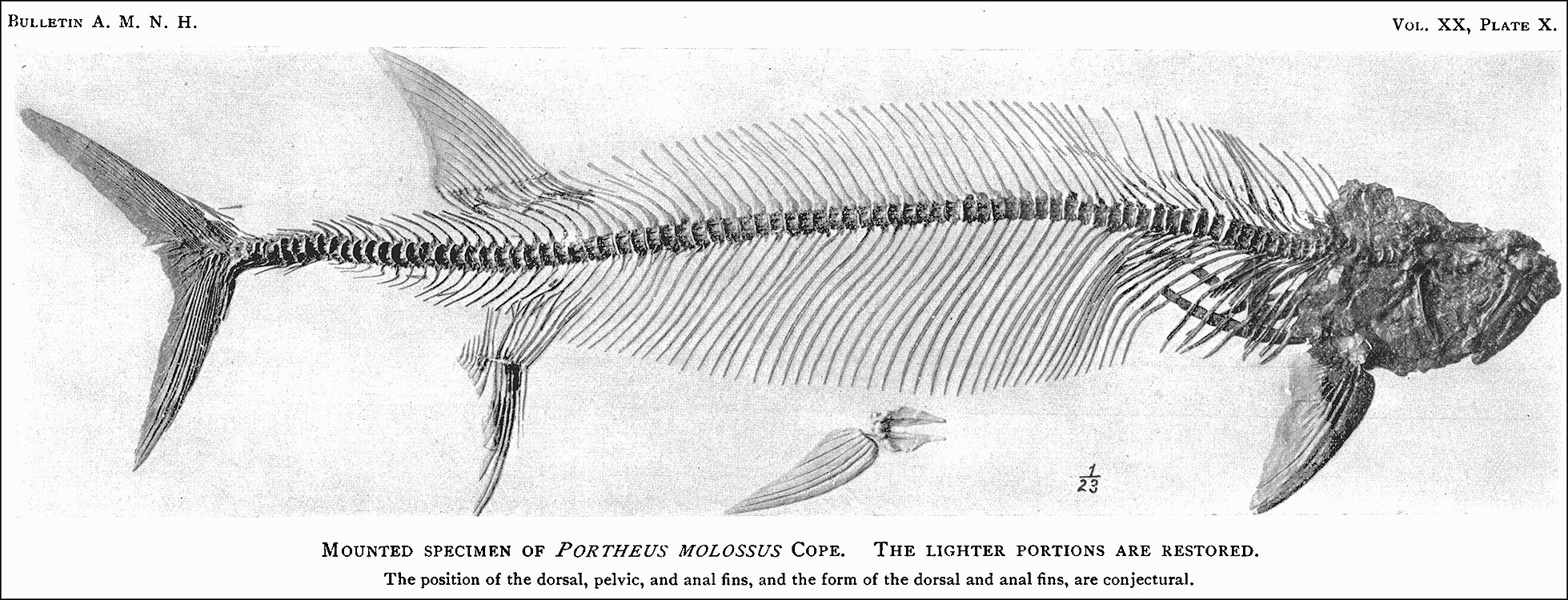

Xiphactinus audax collected in 1901 by Charles and George Sternberg, mislabeled Portheus molossus by Henry Fairfield Osborn. Image from the Oceans of Kansas Paleontology web page, copyright and used with permision of Mike Everhart. Original image at http://oceansofkansas.com/Xiphactinus/Osborn-1904-SpecimenPhoto.jpg.

Fossils are material objects that contain scientific knowledge within them or in their context. Implementing the Public Trust in Paleontological Resources, by Joseph L. Sax, 2001, UCB.

I think of science as a set of explanations for observations, not as a collection of facts. I don't worry when creationists dance around how scientists use the words "fact" and "theory," because science isn't about holding these words sacred. We cannot make facts our gods, because what we say about what we see is always open to questions from other scientists. We must not only stand on the shoulders of giants, but also must be relentlessly questioning the work of those giants.

Microscopes have been tools in laboratories for hundreds of years. When advances come along, scientists can get new information that requires them to re-evaluate prior conclusions, to question the work of giants. Right now we are in the middle of a revolution in microscopy, with many new types of scopes and spectroscopic instruments that have better resolution and offer new non-destructive ways to look at samples. In paleontology we can now revisit specimens, get more information, and question or confirm prior conclusions.

For microscopy in paleontology revisiting fossils requires access to the same specimens the giants looked at--fossils that are held in the public trust at natural history museums.

In paleontology some types of specimens are very rare, such as fossils that show the preservation of soft tissues, very old fossils, or spectacular vertebrate fossils. When describing a taxon, a scientist dealing with these fossils may have only a few to look at. When we get better microscopes that allow us to get higher resolution images or look at a fossil in new ways (Raman, non-destructive XRF), and we draw novel conclusions, we will want to examine the same specimens that other scientists described in the literature, if possible.

Holding a fossil in public trust makes it available for future scientists. Maybe we can now get chemical information from fossils that are too rare or important to have considered taking a destructive thin section in the past. This information may support us in questioning prior conclusions. Or it could confirm the work of other scientists and create a larger set of information.

Kenshu Shimada, a vertebrate paleontologist at DePaul University, recently sent an e-mail to the PaleoNet list servers about the San Diego Natural History Museum's deaccession of vertebrate fossils collected by fossil hunter Charles Hazelius Sternberg. The sale include two fossils that Shimada considers to belong to the public trust. One has since been pulled from sale, but still available, to the highest bidder, is a thirteen foot long Xiphactinus audax fossil from the Cretaceous Niobrara Formation in Western Kansas.

Professor Shimada believes this specimen was used in David Bardack's "Anatomy and evolution of chirocentrid fishes" in The University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions: Article 40 Vertebrata 10. In the paper, Bardack establishes the priority of the genus name Xiphactinus Leidy, 1870 over Portheus Cope, 1871; yes, that Leidy, the teacher, and that Cope, the student, of the Bone Wars Elasmosaurus fiasco, or, rather, scientific re-evaluation. Shimada identifies the specimen as either SDNHM 63.02 or 63.01 in the Bardack paper; 63.02 is my guess.

The San Diego Natural History Museum justifies the sale by stating they had attempted to find a public trust buyer and they will be using the money to purchase local specimens and minerals. An obvious place to offer Sternberg-collected Oceans of Kansas fossils to be kept for public trust would have been the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Kansas, but adjunct curator Mark Everhart says the museum was not offered a chance to buy the fossils (Hays Daily News article).

The San Diego Museum of Natural History is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, and the SDNHM says they are following AAM guidelines for what they buy with the moneys from the sale. I went to the AAM website to see if there are any ethical concerns about the sale of public trust specimens.

"Taken as a whole, museum collections and exhibition materials represent the world's natural and cultural common wealth. As stewards of that wealth, museums are compelled to advance an understanding of all natural forms and of the human experience. It is incumbent on museums to be resources for humankind and in all their activities to foster an informed appreciation of the rich and diverse world we have inherited. It is also incumbent upon [museums] to preserve that inheritance for posterity." AAM Best Practices, Code of Ethics for Museums.

A public sale that disappears important vertebrate fossils into private hands does not preserve the world's natural wealth for posterity.

Fossils contain scientific knowledge. When we get bigger, better, badder microscopes, we can go back and relook at the fossils, and maybe we can get different information or more detailed images that tell an unexpected story about the fish that swam in the Western Interior Sea. This is what scientists do; they observe, and they question the observations of other scientists; technology allows us to observe more than we could see before, but we can't apply that technology to lost fossils. The San Diego Natural History Museum is selling off the public's trust rather than preserving it for posterity.

What can you do?

I have not been keeping up with my list server mails, and the sale is tomorrow. Please contact the museum, their accreditation association, and your congressional representatives in the United States, and question the sale of public trust vertebrate fossils. See if you know someone on the San Diego Natural History Museum's board of directors, or their Binational Advisory Board. The President and CEO is a paleontologist, and they have a botanist on staff. If you know any of these holders of the public trust, please contact them personally and ask questions about this sale. Contact people even if you learn about this after the sale.

See also the article and reader comments at "Historical Fossils May Be Lost at Auction," by Brian Switek, National Geographic.

An earlier articles is "Clashing Titans for Sale -- Dinosaur Skeletons Headed to Auction, Not Museum," by Graham Bowley, The New York Times.

-------------

Three years ago I stayed at my cousin's house in Littleton for GSA. Of course, I had to buy something for her kids, and what could be better than stuffed trilobites. It was a thrill when I handed them over, announced they were "trilobites," and, without another word from me, Marwa, 7, asked her brother if trilobites were older than dinosaurs. Issa, 9, replied, "Oh, Marwa, trilobites are much older than dinosaurs." Not every child grows up with a family heritage of paleontology, and natural history museums are sources of wonder for children of all ages. Sternberg himself prepared this fish fossil, and, yes, I would take an older child in San Diego to see this fossil, if it were still there, and talk about the collectors and the scientists and the bone wars and the wrong heads and the Oceans of Kansas. Maybe I can take Issa and Marwa (now 12 and 10) one day.